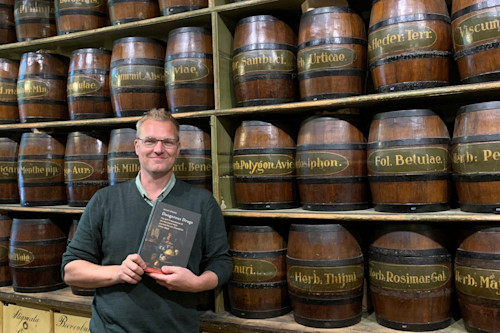

The Points Interview: Ronny Spaans

Describe your book in terms your bartender could understand.

The bartender may already know that aquavit, gin and other spirits flavoured with spices and herbs, were seen as medicines in the Renaissance. But what he probably does not know, and probably will find interesting, is that there was a debate already in the 17th century about whether these “medicines” were dangerous to health. In addition, it probably would come as a surprise that in this debate, terms were used that we today attribute to drug abuse: addiction, hallucinations and moral dangers. And what makes it extra exciting, is that this debate was related to exotic substances. The debate about drugs in the 17th century has much in common with discussions we associate with the history of the spice trade, that is, spices as moral temptations. Exotic drugs could create hot desires in the body, fill you with madness, or make you think you were a king or deity, or they could give you divine insight into forbidden knowledge.

What do you think a bunch of drug and alcohol historians might find particularly interesting about your book?

Drug abuse is not a modern phenomenon, a product of the Industrial Revolution. The types of drugs perceived as dangerous to the human body and to the society have varied from time to time. In the 17th century, incense, precious stones, gold and even mummies (all used as medicine) were considered as just as dangerous as opium and cannabis. The interesting thing here is to look at the moral discourse surrounding early modern drugs, that is, the moral stories that were told by moralists and physicians about them. Brian Cowan has already studied this in the light of the debate about coffee in early modern times, and Benjamin Breen has studied the moral and medical debate about drugs in early modern English and Portuguese culture. In Dangerous Drugs, I study the same phenomenon, but then in the early modern Netherlands, and through analyses of the poems of the drug merchant Joannes Six van Chandelier (1620-1695), who ran the drugstore “The Gilded Unicorn” in Amsterdam. In fact, it is extra worth looking at this in a Dutch context, because the term “drugs” is a loanword borrowed from Dutch: “Drugs” comes from “drogen,” which, simply put, is an abbreviation for “droge waren,” “dry goods,” that is, preserved goods from exotic and mysterious countries. These preserved medicines – whether they were “droge drogen” (“dry drugs”) such as frankincense and amber, or so-called “natte drogen” (“liquid drugs”), such as oils and essences, were thus seen as opposed to fresh herbs from the local pharmacy garden. That is why in the Netherlands we probably find the most interesting debate about drug use and abuse in the early modern period, which is probably not surprising in terms of the liberal drug culture in the Netherlands today, and in terms of the Dutch colonial history. As I said, this debate has many common features to the discussion on spice history. In the poems of Joannes Six van Chandelier, “drugs” and “spices” are used as a synonym.

Six’s poems are incredibly exciting in this context, because the poet thematises drug use in many different fields of society: drugs as a status symbols in the cabinet of curiosities, drugs as remedies, drugs as dyestuffs and cosmetics, and drugs as linguistic ornaments in the renaissance poetry. Six himself suffered from a disease, which he related to the contact with drugs, and he was influenced by a Calvinistic pietism, which demanded a self-examination linked to all aspects of life, also to his activities as a spice merchant.

The druggist’s wares I have been studying have previously been scrutinized in the light of iconology. For example, shells, bones and smoke have been seen as symbols of memento mori and vanitas. However, I have chosen to see what physicians write as these luxury goods, because the materials also appear in medical and pharmaceutical works in the early modern period. And in these works, the original meaning of ”drug” – exotic, preserved commodity – determines the perception of these products. Physicians and scholars argued over what was healthy: expensive exotic luxury medicines, or local herbs. This was this a struggle with a social and ecological commitment. We recognize many arguments from our own discussions of ecology, and on the local food movement, as an alternative to the global food model. Drugs were also seen as a psychologically transforming agents and linked to concepts as addiction, intoxication, and social unrest–notions we thus know from today’s debate on drug abuse. In fact, we also recognize concepts from the debate about genetic engineering, for moralists thought that drugs could change the inner and outer character of a human being. They could make man perfect. This had not least theological implications, with a view to the notion of man as God’s work of creation. Six van Chandelier is particularly interested in drugs as a means of apotheosis in various fields of society, whether it is religion, alchemy, or in art and literature related to the royal cult of early modern European courts.

Now that the hard part is over, what is the thing YOU find most interesting about your book?

The interesting thing is that Six does not list religious dogmas against drug abuse, but writes stories about how he as a spice merchant is challenged by moral dilemmas associated by different exotic drugs. These stories are written in a creative and humorous way, and often in an everyday setting. For example, he writes about how he is offered a new product on a business trip in Spain: an exotic horn, but this time it is not a horn from a foreign animal, but the horn of a “hornbearer,” a cuckold (the burlesque humour of this poem is typical of the 17th century, compare for instance Jan Steen’s paintings). In another poem, he tells how he foams at his mouth when he writes ecstatic, panegyric poems to the Prince of Orange. This poem is addressed to both Six’s personal doctor and to his pastor. The most conspicuous text in Six’s book of poems is printed in red ink and is a listing of all the expensive red drugs that can be found on the Dutch market. A drug surpasses them all, the blood of King Charles I, who was executed in 1649. This product will give you divine ecstasy and fulfill your deepest dreams, the poet writes. Among other things, the blood is compared to the Tyrian purple, known from the imperial cult of the Roman Empire. The fantasies linked to this wonder blood make us think on “The Perfume” by Patrick Süskind! But of course it is an ironic poem – the seller of the miraculous blood is compared to Judas.

Every research project leaves some stones unturned. What stone are you most curious to see turned over soon?

During this research project, I have, with the help of historians, discovered many unknown sources in Dutch archives about the trading activities of Six. But Six was a traveling spice merchant in Europe and there are still undiscovered documents about him in Spanish and Italian archives. They can shed new light on the authorship.

And then there should be done a more systematic analysis of the concepts of drug in the early modern Netherlands. Here, the starting point must be the moral discourse around drugs, the discussion on “groene en droge kruiden” (“fresh and dry spices”). One hypothesis in my work is that humanist and Christian arguments against spices and perfumes led to their downfall as medicines, and contributed to an important shift in early modern natural science, from a drug lore based on mythical and fabulous concepts, to a botany based on observation and systematic examination. Normally this shift is related to the discovery of the true chemical properties of plants, revealed through empirical modern chemistry. I argue, on the other hand, that the stories about them as morally reprehensible products also play a role in this shift.

BONUS QUESTION: In an audio version of the book, who should provide the narration?

Well, I rather see the poems of Joannes Six van Chandelier than my book transformed into – not an audio book – but a fiction film. Six was a Calvinist placed in the midst of an internal conflict between the appeal for renunciation and self-examination on the one hand, and the temptations of spices and drugs on the other hand. His poems, which have a surprisingly narrative and autobiographical character, could form a starting point for a good film adaptation of his life. Willem Dafoe did a good job when he played Vincent van Gogh in At Eternity’s Gate. He would also be the right man to play the role of the “Vincent van Gogh” of early modern Dutch poetry, Joannes Six van Chandelier.

About Points

Points is an academic group blog that brings together scholars with wide-ranging expertise with the goal of producing original and thoughtful reflections on the history of alcohol and drugs, the web of policy surrounding them, and their place in popular culture. A group blog provides a space for the exchange of new ideas, insights, and speculations about our interdisciplinary and rapidly evolving field.

About the Author

Dr. Ronny Spaans is Associate Professor in Nordic Literature at Nord University. He also teaches Dutch at the University of Oslo. He obtained his PhD from the University of Oslo on a thesis on the poetry of Joannes Six van Chandelier (2015).