The Colour Fantastic: Two Decades of Research into the Colours of Silent Cinema

Fossati Fantastic

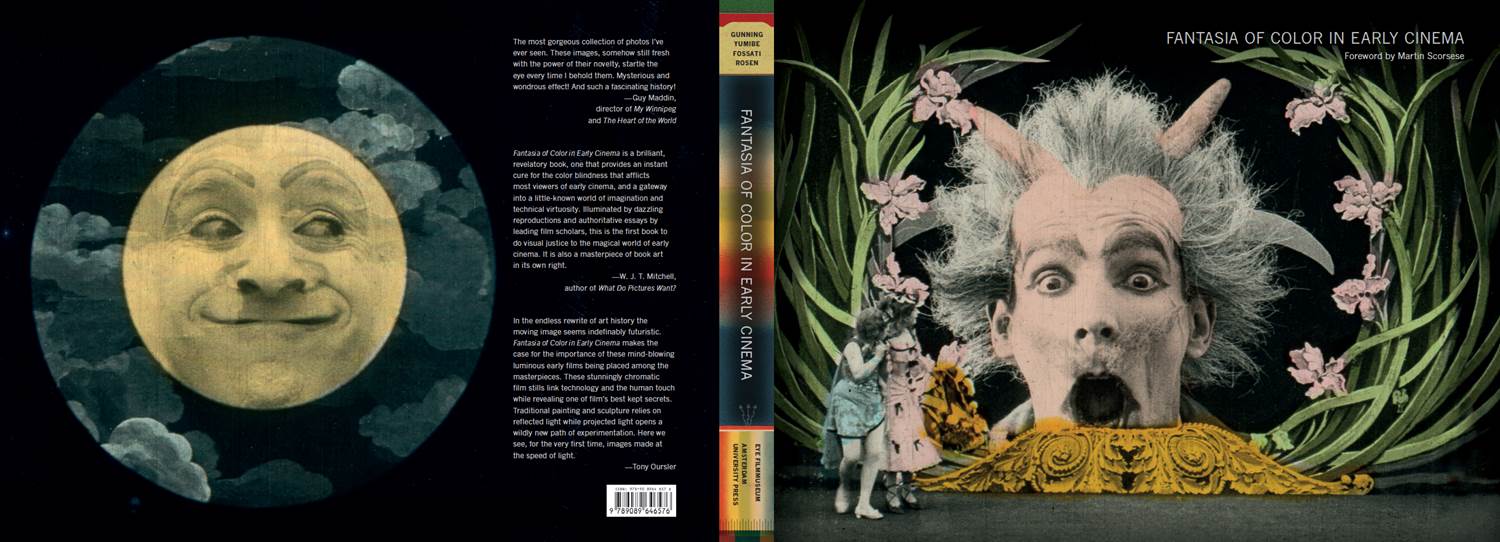

Giovanna Fossati, Victoria Jackson, Bregt Lameris, Elif Rongen, Sarah Street, and Josh Yumibe. These are the volume editors of The Colour Fantastic, the latest book in the Framing Film series at Amsterdam University Press. Published in April, three years after the Fantasia of Color in Early Cinema (the beautiful trailer of which you can watch below), this collection of essays brings together international experts to explore archival restoration, colour film technology, colour theory, and experimental film alongside beautifully saturated images of silent cinema.

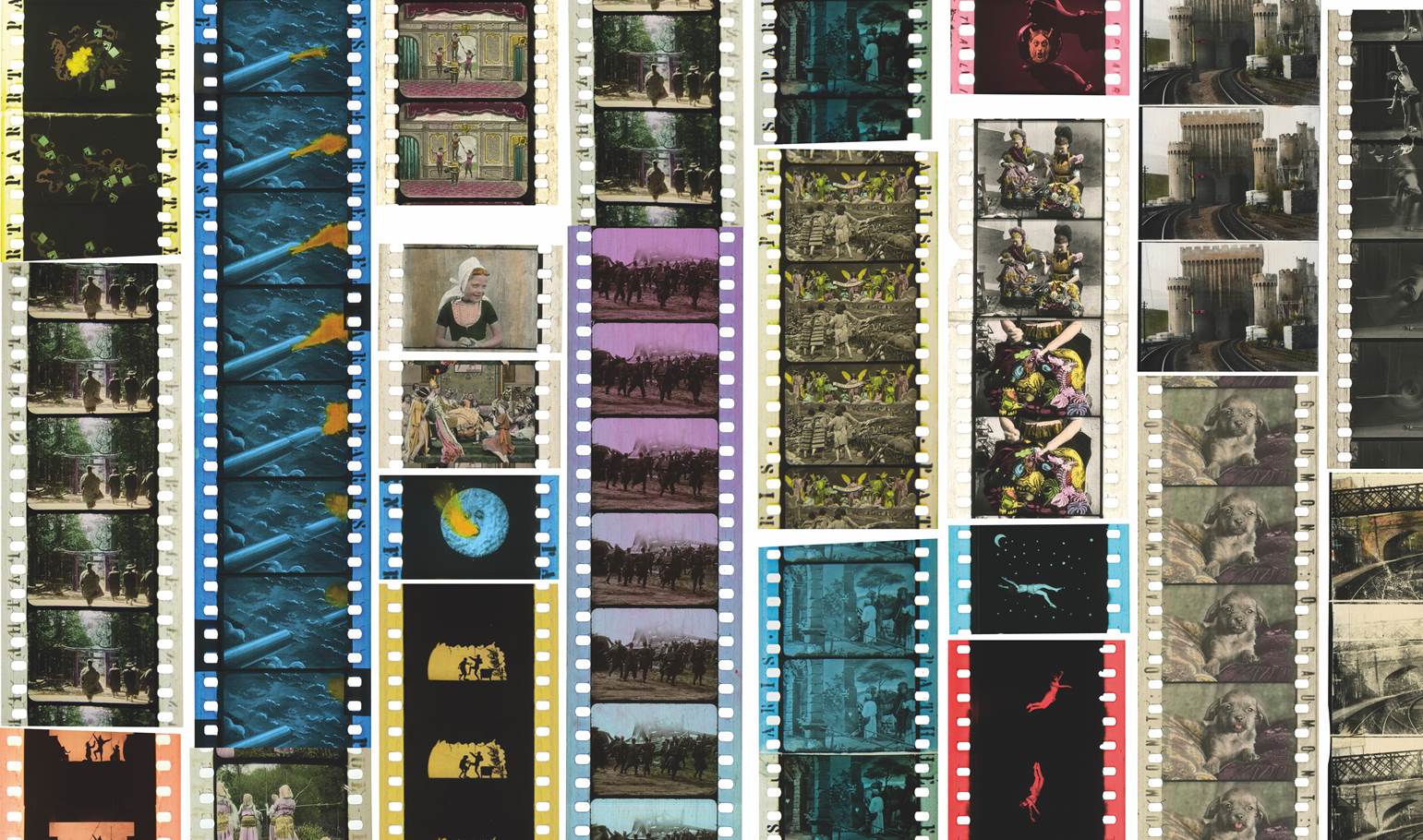

The mesmerising images in The Colour Fantastic are evidence of colour as a crucial aspect of film form, technology and aesthetics, as this book explores, following the spark of scholars and archivists inspired by the groundbreaking Amsterdam workshop titled “Disorderly Order: Colours in Silent Film”. Giovanna has worked on several books with AUP; alongside her roles as Chief Curator at the Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam, and Professor of Film Heritage and Digital Film Culture at the University of Amsterdam, she is a series editor of the Framing Film series, author of From Grain to Pixel (a revised edition is forthcoming this year), co-author of Fantasia of Color in Early Cinema with Tom Gunning, Joshua Yumibe, and Jonathon Rosen, and co-editor with Annie van den Oever of Exposing the Film Apparatus – she is, to AUP, Fossati Fantastic.

In March, Giovanna gave a keynote lecture at the Third International Conference ‘Colour in Film’, held at the BFI in London. AUP are pleased to be able to publish Giovanna’s keynote here, alongside a small selection of images from The Colour Fantastic, and a short programme of silent colour films from the Eye collection. Her talk covered four topics from a personal perspective on twenty years of research on colour in silent cinema. She illustrates the books The Colour Fantastic and Fantasia of Color in Early Cinema, and two research projects on digitized film collections, Mapping Desmet and The Sensory Moving Image Archive, and the contexts from which they emerged. For Giovanna, colour in silent cinema has become a returning topic in her professional life from its beginning more than twenty years ago, both as an archivist and a scholar. As such, she approaches this keynote in an autobiographical manner, having developed a personal connection with the topic than transcends a purely academic approach.

The Keynote

My first job in a film archive was in 1995 when I was a student in Bologna and I was accepted as an intern at the Nederlands Filmmuseum (today Eye Filmmuseum) to research colour in silent film in preparation of an international workshop on the topic.

Without internet, e-mail and mobile phones, I had all the time in the world and I spent 8 months viewing coloured nitrate films and reading about early colour techniques in handbooks and journals from the time when such techniques were so pervasively used. Thanks to Daan Hertogs and Nico de Klerk, who at the time worked at the Nederlands Filmmuseum, I was deeply involved with the programming and organisation of the workshop on colours in silent film, which was held in July 1995.

As ‘Disorderly Order’, the resulting book publication based on the Workshop explains, colours in the plural were conceptually very important because of “the variety of colours that adorned the films and film programmes of the silent era, by the various ways in which these colours were applied to the film material, and (no less importantly) by the various transformations these colours have undergone and are still undergoing”.

What emerged from the 1995 workshop has so profoundly influenced colour research for the past two decades, including the work of many people who are still researching this topic.

Besides my own experience, I would like to mention that the colour workshop proceedings inspired Joshua Yumibe to take up color in early cinema as a PhD project, which eventually culminated in his book Moving Color. The workshop has also been a guiding influence on the collaborative research project, Colour in the 1920s: Cinema and Its Intermedial Contexts, led by Yumibe and Sarah Street. And it has been a vital context for the authors of the illustrated publication Fantasia of Color in Early Cinema that I will discuss later.

The Colour Fantastic: The Conference

It is the interdisciplinarity of that collaborative and sharpening work that has guided Sarah Street, Joshua Yumibe, Bregt Lameris, Vicky Jackson, Elif Rongen-Kaynakci and myself in organizing the conference.

The Colour Fantastic: Chromatic Worlds of Silent Cinema, which took place in 2015 at Eye Filmmuseum

There, we aimed at moving back and forth from a historical archive of chromatic riches to our present day engagement with it – to examine both what the cultural and technological world was that produced moving color images a century ago, and how those hues can still speak to our contemporary and increasingly digitised environment.

The conference celebrated the twentieth year anniversary of the Workshop Colours in Silent Film by providing a new forum to explore contemporary archival and academic debates around colour in the silent era.

Before 1995, the use of colour in silent cinema was for many years a neglected aspect of film history. Thanks to the 1995 workshop and to the attention given to the topic by film festivals such as Il Cinema Ritrovato and Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, and the restoration practice of archives such as La Cineteca di Bologna and its laboratory L’Immagine Ritrovata, the Royal Film Archive in Belgium and the Nederlands Filmmuseum and its partner laboratory Haghefilm, the last twenty years have seen the topic receive increasing attention from scholars and archivists. The success of this conference also attests to such increasing attention.

The Colour Fantastic: The Book

The publication The Colour Fantastic reflects on the 1995 workshop, revisiting key topics from the original event and looking at how more recent research sheds light on these issues. In addition, it considers the new directions research into silent colour has taken by exploring a diverse range of archival and academic topics.

The examination of colour in cinema during the silent period remains significant today particularly in light of the digital turn that has seen not only an explosion of colours in new digital media but has also transformed the options for preserving and restoring the chromatic elements of film and media.

The Colour Fantastic features a selection of essays originally presented at the 2015 conference. The 12 essays contained in the book are divided into four thematic sections, you can download the Table of Contents and Introduction here.

The book’s Prologue is provided by Peter Delpeut’s contribution ‘Questions of Colours: Taking Sides’. Delpeut revisits the turbulent years when he was the Artistic Deputy Director of the Nederlands Filmmuseum (1988–1995) and recalls the reasons that led a new generation of film archivists to purposely break with archival tradition by unearthing hidden aspects of film history such as the colours of silent cinema. In the spirit of the Disorderly Order publication of the 1995 workshop, we also included the edited transcripts of the two Archival Panels we had at the 2015 conference on Preservation, Digital Restoration, and Presentation aspects.

During the 2015 conference, as yet another reference to the 1995 workshop, we chose to open all sessions with a short screening of silent colour films from the Eye Collection. All screenings then were accompanied by Stephen Horne and I am very happy that he is with us today to accompany this short compilation as he did in 2015.

Screening Colour Fantastic Conference

- Les Parisiennes (US, 1897, American Mutoscope Company)

- Narren-grappen (US, 1908, Joker Film)

- Opus III (D, Walter Ruttmann, 1925, Ruttmann-Film)

Fantasia of Color in Early Cinema

As a manner of introduction to the second topic I will address today, the project and publication Fantasia of Color in Early Cinema, I would like to briefly touch upon a development in film heritage studies that has been one of the factors that triggered this project and has become, more generally, of great influence on the way we research, preserve, restore and present silent colour films today.

I am talking about the so-called ‘material turn’, a development that is taking place in the larger landscape of film and is deeply affecting the film heritage discourse. The material turn can be defined as a renewed longing for the experience of the materiality of the film medium.

This can be found in work by filmmakers and artists alike, including Gustav Deutsch, Bill Morrison, Tacita Dean and many more.

Such longing for materiality in a time when digitization has become so pervasive, is probably due to a stronger desire to be in direct contact with objects, especially historical ones, and with their material qualities.

This phenomenon has been defined as the “material turn” within various disciplines and is becoming an important new stream within media and film studies.

In her seminal paper “Material properties of historical film in the digital age”, Barbara Flueckinger discusses film as an object and points out that:

“Beyond mere visual inspection, the film’s material body is very tangible to all the senses. It accumulates olfactory, haptic, and even acoustic dimensions, each of which form part of this singular element’s authenticity.” (p.8, 2012)

The discussion on the “material turn” is also having repercussions on long-term digital preservation and, in this respect, the ERC project Film Colors, led by Barbara Flückiger at the University of Zurich, should be mentioned for its important aim at addressing the need to preserve specific historical and aesthetical characteristics of the original analog film, in particular in relation to historical color systems.

In my view, the material turn is intrinsically related to the digital turn, but is not in opposition to it. It is rather its companion. In fact, there is no such thing as immaterial digital film. A digital film is as material as any other object. It is carried on a material carrier, it is projected through a material digital projector and screened on a material screen or viewed through a device. And it is immersed in a material cultural environment, that of its makers, users and caretakers, like analog film, before. In this line of reasoning, digital films are the result of a tradition of a century of analog films and as such they bear the same material and cultural traces, and digitization is not a replacement but the latest technological shift.

It is this combination of a new longing for materiality and new perspectives offered by digital means that led to the project and publication Fantasia of Color in Early Cinema.

Besides the book, this international collaboration between Tom Gunning, Joshua Yumibe, Jonathon Rosen, Elif Rongen-Kaynakci, Guy Edmonds and myself led also to the creation of a collection of digitized high-resolution scans and a film program that has been touring around the world at festivals and cinematheques in the last three years. The book contains 250 full-page frame scans, four essays, and an annotated filmography. The scans were made directly from original coloured nitrate frames held at EYE Filmmuseum at the high resolution of 5K or 4800 dpi.

I like to think that it all started 20 years ago when Tom Gunning and I first met at the already mentioned Amsterdam workshop in 1995. Since then we kept discussing our mutual fascination for these films and their exceptional applied colours.In 2009, during Le Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone, Tom discussed his idea for an illustrated book on early color cinema with Joshua Yumibe and me. Soon after that, Amsterdam University Press and Eye Filmmuseum expressed their interest in publishing the book and so we started working on it.

In my essay in the book, I focus on the archival life of early colour films, that is the different ways in which these films have been restored and presented during the past 30 years, and on the new possibilities that are arising today with digital tools. As for the choice of enlarged high- resolution scans of single frames, I argue that this specific presentation form addresses the current increasing demand for access to film heritage. Furthermore, it offers a much closer access to the original film material than any screening (in the cinema or on a monitor) could allow, as it is at higher resolution and it is still.

Although early color films nowadays can be found online and have been celebrated by Martin Scorsese’s Hugo, only film archivists and scholars have the opportunity to spend time looking at these films, frame by frame, and appreciate their unique material quality. With this book we aimed at making this experience possible for everyone.

The project Fantasia of Color in Early Cinema has literally focused on a very limited selection of objects, namely film frames, from a film collection at high resolution. And this is unquestionably a different kind of access, and thus experience, than viewing hundreds of thousands of film frames condensed in compressed videos online or in colour visualisations such as those produced in the framework of the projects I am going to discuss in a second.

Still, other tools for access and research are also needed to help us reassess anecdotal methods, find new research questions and make film collections known by and accessible to a broader range of researchers, artists and audiences.

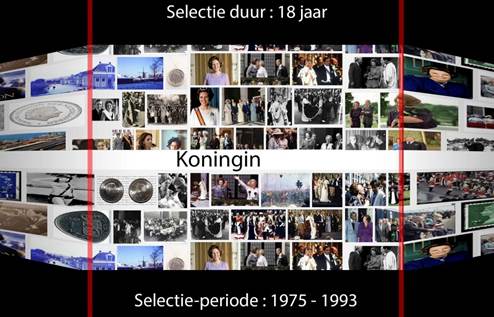

In this line, I believe in the importance of complementing qualitative analysis of singularity and materiality of media objects with big data quantitative research such as in the case of the project Data-Driven Film History: a demonstrator of EYE’s Jean Desmet collection, also known as the Mapping Desmet project.

Mapping Desmet has been carried out in 2014 and 2015 by researchers at the universities of Amsterdam and Utrecht, staff from EYE, and two IT and creative industry partners. The project’s aim was to devise tools for visualizing and mapping the distribution, screening and stylistic features of the films in the Desmet collection, by using three different datasets and creating rich links between them in a mapping interface.

The Desmet Collection is held at Eye Filmmuseum and contains the archives left behind by the Dutch film distributor and cinema owner Jean Desmet. This collection consists of approximately 950 films produced between 1907 and 1916, a business archive of more than 100.000 documents, some 1050 posters and around 1500 photos. Because of its historical value, the Desmet Collection was inscribed in UNESCO’s Memory of the World register in 2011.

The Research Project, ‘Data-driven Film History: a Demonstrator of EYE’s Jean Desmet Collection’

- Funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) in the Creative Industries Program

- University of Amsterdam: Giovanna Fossati (PI), Julia Noordegraaf, Eef Masson, Christian Olesen

- Utrecht University: Jasmijn Van Gorp

- Eye Filmmuseum (data provider), Dispectu (technology provider), Hiro (technology provider)

http://mappingdesmet.humanities.uva.nl/

http://mappingdesmet.humanities.uva.nl/

In particular, we wanted to test the usefulness of such tools in establishing relations between the distribution and screening of the films, and between their screening and some of their aesthetic qualities, specifically their use of colour. Our main goal in developing the mapping tool was to visualize the geographical patterns behind the distribution and screening of films owned by Jean Desmet.

By providing macro-visualisations of their distribution and screening, vis-à-vis micro-descriptions of the individual films, we aimed at reuniting all available information with regard to the collection in a single mapping that could facilitate the navigation of such an abundance of information, but also inspire new research directions.

Experimental component: Colour Visualisations

- How can we combine textual and contextual approaches to gain new insights into film colour history?

- In the long run: show developments in film colours over time

- ImageJ visualisations: Slitscan, Montage, Summary

- http://www.create.humanities.uva.nl/results/desmetdatasets/

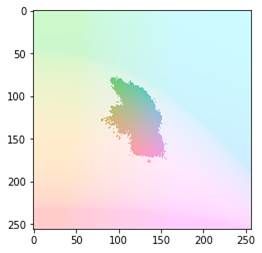

In addition to developing a mapping tool, we were prompted by the Desmet collection's significance for film colour historiography to also experiment with tools for colour analysis.

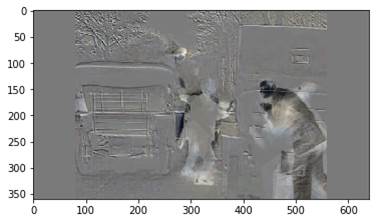

Using the open-source visual analytics software ImagePlot - developed by media theorist Lev Manovich as an extension of the medical imaging software ImageJ - film scholar Christian Olesen visualized a select number of films, with the ultimate goal of linking our results to our mapping interface.

Using ImagePlot, each of the video files at our disposal was broken down into sequences of 100.000+ images, consisting of all the films’ frames. From these sequences, Olesen created different types of visualizations so as to find out which kinds of patterns each would reveal. Eventually, we hope, this may allow users to relate the macroscopic perspective of a map and its visualization of distribution networks to the microscopic colour features of a film or film programme, through one and the same interface.

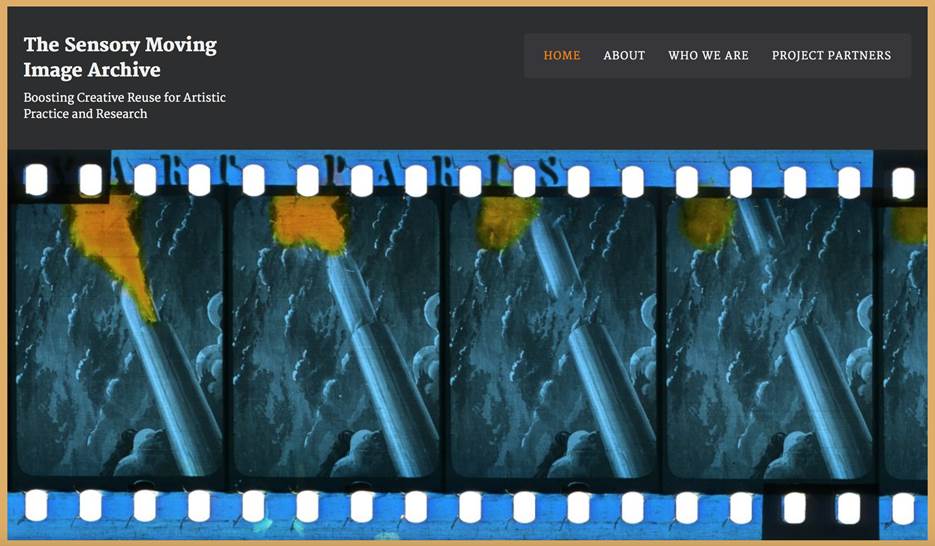

As a follow-up to the experimentations within the Mapping Desmet project, we inititiated the project “The Sensory Moving Image Archive. Boosting Creative Reuse for Artistic Practice and Research” in 2017.

The Sensory Moving Image Archive (aka SEMIA) brings together a broad spectrum of disciplines, including media and heritage studies, digital humanities, informatics, application design, and professionals from AV-heritage institutions and from the Creative Industry.

What

Users want to explore heritage collections with tools that can support their creative process.

Who

3 groups of creative users:

- artists (media & data art)

- creative industry (heritage field)

- researchers (media history)

How

- explore collections

- through sensory (in particular visual) relations

- complementary to existing searching tools (semantic search)

Our main goal is to develop ways to allow free explorations of digitised AV collections for artists, the creative industry, and researchers. More specifically, we want to research which means are necessary for users to be able to explore collections through sensory relations, in particular visual ones.

Descriptive metadata and semantic analysis

Heritage institutions typically make their collections accessible through semantic searches. In other words, users can search using descriptive metadata as they have been compiled in the catalogues of heritage institutions.

The basis of such searching methods are the interpretations that have been associated with the material, and the assumption that users already know what they are looking for.

Data artist Geert Mul, for instance, applies such a strategy in his installation illustrated in this slide. In this work image combinations are generated based on semantic analysis.

Image of the installation Ander Nieuws* (Geert Mul/Sound and Vision)

Description from online catalogue Sound & Vision

Visual analysis based on sensory relations

The project SEMIA investigates how existing semantic analysis can be supplemented by exploration of collections based on sensory features of the material. Examples are light and colour, forms, or movements in the image.

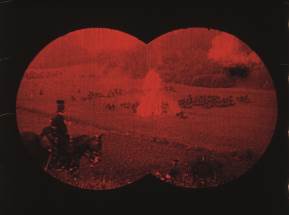

Stills from De molens die juichen en weenen (NL 1912), De Bertha, Louis Hendricus Chrispijn sr. (1913, NL) en Maudite soit la guerre (BE 1914), from the Eye collection

Media researchers

Researchers can benefit from sensory exploration when studying patterns in the use of colour techniques, or in the use of conventional masking shapes, in a specific historical timeframe.

These kind of questions cannot be answered only based on the researcher’s memory (when watching a great amount of archival films), but also not with the information that can be found in the catalogues.

What is maybe even more important is that visual analysis can help discover patterns that we are not even aware of. The relations between colors and shapes in these images are obvious examples of such patterns.

Artists

For artists, the advantage of visual analysis is that they can establish realtionships within a large amount of materials. Such relations can then be creatively exploited. In addition, visual analysis allows a more independent connection with the material.

In the found footage film Aurora Goes to Holland, Jonathon Rosen was inspired by pure visual relations but he had to choose from a relatively small amount of material from the Eye collection selected by a curator who served as a gatekeeper. Visual analysis makes that pre-selection in principle unnecessary.

Research Workshops and Symposium

- SEMIA Workshop 1: Digital Methods in Media History

- SEMIA Workshop 2: Visualizations & Interfaces

- SEMIA International Symposium 2019

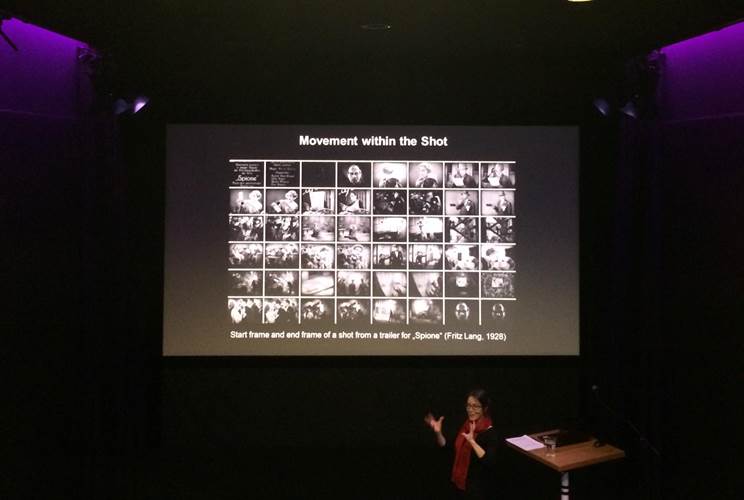

The way we going to do this is, in the first place, through interdisciplinary workshops, which aim to nurture the exchange of ideas between the different user groups. In the first SEMIA Workshop, held last month in Amsterdam, we aimed at sketching an overview of state-of-the-art image feature extraction and visual analysis in media historical research and the digital humanities. The workshop’s main questions were how we extract visual data, what procedures are in use and what results we can achieve with them?

We chose to focus on 3 different image features that we consider essential to our analysis: Colour, Movement and Texture. A big emphasis was also given to the collaboration between computer scientists and humanists. While the focus of the workshop was mainly media historical, we also sought input from media artists, in particular those who work artistically with data visualizations and who will challenge the evidentiary image analysis of media historians.

The second SEMIA Workshop will take place next week and will focus on Visualizations & Interfaces. There the artists we work with will take a lead in discussing how to visualize the data we have extracted and discuss the development of presentation formats and interfaces which can suit the need of both media historians and artists.

Current research activities

UvA Informatics Testing computational methods on Desmet Films: Analysis of colour space and movement

In this phase we are still finding a way to communicate between the different team members, especially the Humanities scholars and the computer scientists for the purpose of defining analytical focal points. The Informatics partners are testing computational methods on an initial collection of 300 digitized high resolution titles from the Desmet Collection. The images above show two very early attempts to analyse colour space and movement.

These are just first steps. If you like to follow this project, please visit our website at sensorymovingimagearchive.humanities.uva.nl.

Biography

Giovanna Fossati is Chief Curator at EYE Filmmuseum and Professor Film Heritage and Digital Film Culture at the University of Amsterdam.